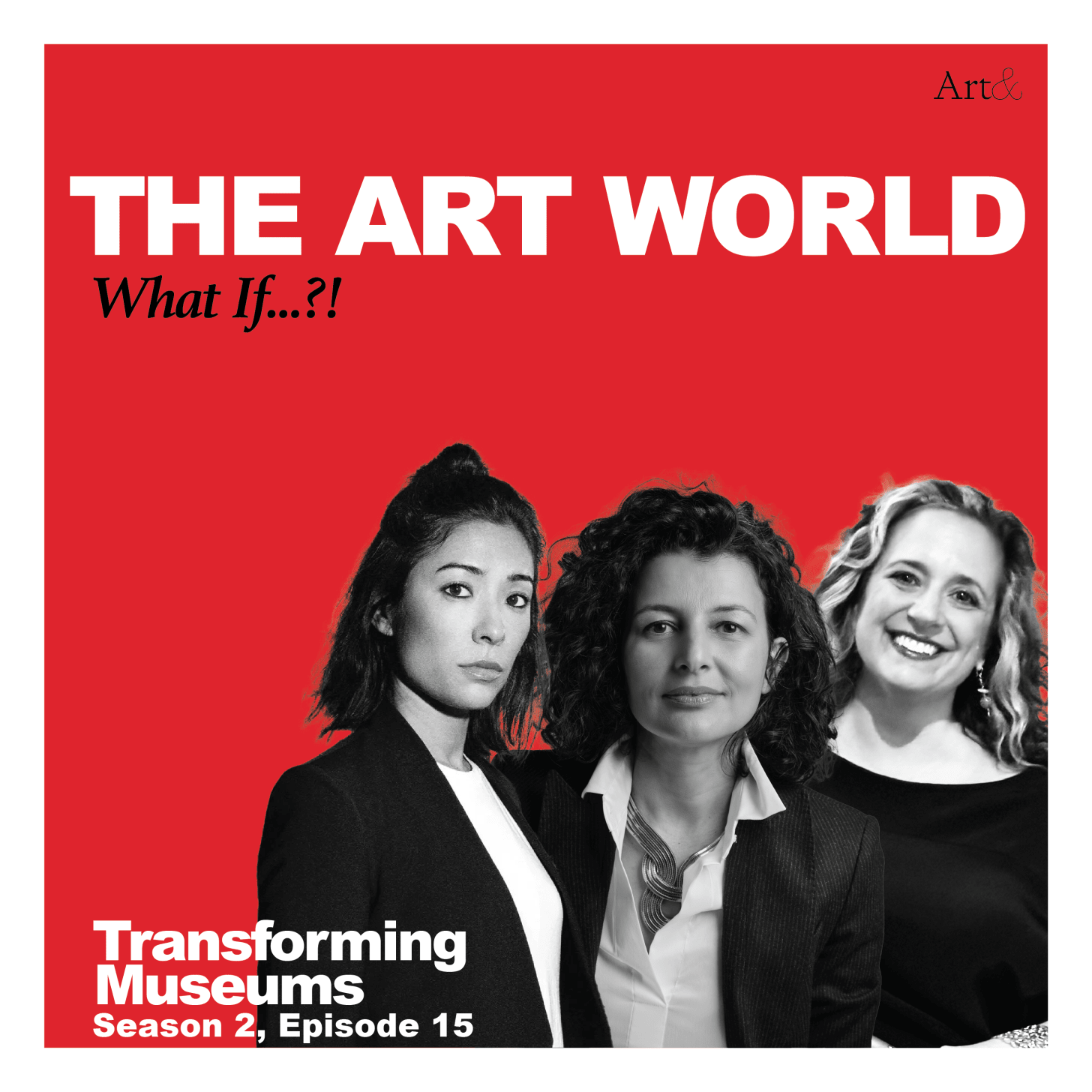

Photo credits: Pari Dukovic for the New Yorker (Mia Locks), Christa Holka (Fatoş Üstek), and Laura Raoicovich.

What if you were embroiled in a public workplace controversy? And what happens on the other side of the headlines—would you walk away from your field, or would you reengage with it to try and improve upon it?

This very special episode is a break from the norm. In it, we discuss museums and change—and what it takes to get to that change. We’re joined by three curators—Mia Locks, director and co-founder of Museums Moving Forward; Fatoş Üstek, curator and former director of the Liverpool Biennial; and Laura Raicovich, writer, curator, and former president and executive director of the Queens Museum. Each of them has been through a public furor. In those moments, they have found a lack of institutional support and, afterward, each has shifted from their previous career paths. But each has re-engaged with the field in more ambitious and ultimately hopeful ways. Museums can't be taken for granted. But what does it take to create change? Tune in now for more.

Charlotte Burns: Hello and welcome to The Art World: What If..?! This is a show all about imagining new futures. I'm your host, Charlotte Burns.

[Audio of guests]

This is a different kind of episode. We thought we'd experiment with a show about museums and change. It's also about how you get to that change. What if you were embroiled in the kind of controversy that could scorch your reputation, your career, and your income? How does it get to that? How do things escalate? And what happens on the other side of the headlines? What if you could walk through that fire and survive? And instead of turning your back on a field that had burned you, what if you decided to reengage with it to try and improve it? Would you?

We're going to talk to three guests in this episode who've done just that. Each of them is a curator who's been through some kind of professional, public, media, and online furor. Each of them has, in those moments, found a lack of institutional support. And each, after the crisis, has had to shift career path. But instead of leaving the field, they're wholly committed to improving it, which is interesting and I wanted to go into that instinct and ask them, why? And what it is they're proposing instead.

Having grappled with the scope and scale of what's at stake, our guests have reemerged in more ambitious, ultimately positive ways. They are trying to create profound and very considered change rooted in what they think needs doing, and what they think can be done. These interviews were also a helpful reminder that while it can feel like this period of extreme politics and polarization is new, it's actually been long enough that people in our field have been through these fires, written books, regrouped, and galvanized. We have more experience and capacity than we think, particularly in the realm of culture, which, at its best, can hold a lot of space for complexity.

But museums can't be taken for granted. The people who work inside them, including their leaders, are increasingly sounding an alarm. Our guests in this episode are both witness to the dysfunction but also offer some hope and new ways forward.

So, what if? Let’s get going.

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: First, I wanted to know how it feels to go through that fire, which is a fear for so many people, and what then compels you to reengage with the field on the other side.

Our first guest is Mia Locks, director and co-founder of Museums Moving Forward, which is an organization founded by curators. Its mission is to create a more just and equitable museum sector by improving the workplace.

Mia, who’s also one of our editorial advisors on the podcast, was the co-curator of the 2017 Whitney Biennial. It was one of the most controversial in recent memory for its inclusion of Open Casket, a painting by Dana Schutz of Emmett Till. There were protests and calls for the work to be removed and destroyed.

Several years later, in 2021 Mia, who’s been widely heralded as one of the country's most prominent curators, resigned from her position as senior curator and head of new initiatives at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, saying that she met resistance to the diversity and equity initiatives she’d started there.

[Excerpt from interview with Mia Locks]

Charlotte Burns: What if you can go through what is a massive fear for most people, that sort of public professional maelstrom, and come through it? Do you feel less fear on the other side?

Mia Locks: That's an interesting question. I mean, I think a lot of people fear public scrutiny. I don't think anybody I know wants to be involved in a controversy of any kind. I do think something happens when you go through that. It's very humbling to have people out there criticizing decisions you've made. They say all kinds of stuff about you. You learn that first of all, you can't please everybody. And you learn that this is actually a profoundly human thing; that every human is like, “Oh, I said a thing or did a thing and now I'm not sure it was the thing I meant, or I'd love to reconsider it.”

Once you've gone through something like that in the public eye, yeah, it's humbling. There's some people that could respond to an experience like that by hiding under a rock for the rest of their lives or deciding to have some sort of explosive emotional response. But, for most of us, especially those of us that are really invested in museums and this idea that art is essential and that museums, at their best, help us figure out how to be in the world, that actually going through something like that is not unlike what we hope we experience in the museum, which is gathering together to experience difference or confusion or awe or disgust, what have you, and learning to engage with each other in that process. I guess for me, nothing else in the world has given me that other than art. Like art's been the baggiest thing to hold all of that.

Yeah, I guess maybe that is a fear for people to have to do that publicly. But I don't know. I'm not sure if there's less fear on the other side. Like all things, when it's a bit of, like, the fear of the unknown, it's scary, but then we do it, and maybe it's slightly less scary because now we have some sense of what it is.

Charlotte Burns: Our second guest, the writer and curator Laura Raicovich, is the former president and executive director of the Queens Museum in New York. She resigned in 2018 after tumultuous years in which national politics took center stage.

[Excerpt from interview with Laura Raicovich]

Charlotte Burns: You wrote in your book, Culture Strike: Art and Museums in an Age of Protest, and I'm going to quote you here: “As I know from personal experience, fear often pervades the staff at the museum during controversy at all levels. This fear is partially tied to the possibility of internal retribution, but also connected to a larger and more insidious dread, a fear of public failure. Revealing any vulnerability or uncertainty in the face of critique can be overwhelming, given the perceived precarity within an institution. If only this fear of public failure—which would presumably result in the threat of exclusion from museum work—could be mitigated by the realization that courage and vulnerability are one in the same, we might be able to imagine better museums.”

Laura, I was really struck by the fact that having been through this very public fire, you've come through the other side and have been determined to imagine better museums, as have the other guests in this episode. And I wonder what it is that's compelled you to engage with the field in that way?

Laura Raicovich: Thank you for this question. It's a really important piece of my own journey, actually. It was pretty much inconceivable for me to not be a museum worker or cultural worker that was inside of an institution before leaving the Queens Museum and finding my situation there untenable. And I think for me, the power of culture and art to help us imagine other realities is at the core of what keeps me in the game, as it were.

At the end of the day, I really believe in the power of culture and the power of what art does in our minds, in our hearts, and our imaginations to actually bring us to a different way of perceiving the world, of understanding our place in it and that is why I stick around. I still really believe in that power. And I definitely get frustrated at the moves that cultural institutions make. Maybe I don't have as much faith in these spaces as I used to, but I have faith in what the art that's their main charge does in the world. And that's where I think my stubbornness persists.

Charlotte Burns: I spoke to Fatoş Üstek who stepped down as director of the Liverpool Biennial in 2020 following a dispute with the board. Two trustees stepped down in solidarity, protesting the board's treatment of Üstek.

[Excerpt from interview with Fatoş Üstek]

Charlotte Burns: Can you talk a little bit about what happened with Liverpool, and what you learned through that experience?

Fatoş Üstek: So it was also published widely. What happened was a clash between members of the board and myself at a time of major crisis erupting in the world, the global pandemic. But I think what happened was that there were gaps and cracks in the structure and how the organization operated that kind of accentuated themselves. There was also a confusion of roles and responsibilities and the organization ended up literally not enabling me to do the work I wanted to do and to also actualize the vision I built and I was celebrated for by the board in the first place.

Charlotte Burns: Looking back on that now, how do you feel about that time? Do you feel that it's changed your practice?

Fatoş Üstek: It has definitely changed my practice. At the time, as a director of Liverpool Biennial, I think that is the most lonely I felt in my whole career. I've learned a lot. I think I could say that I'm a better person, a better manager. And I also now understand where I need to make people accountable and responsible for their positions. I'm someone who reflects and also finds mistakes, like what was my contribution? How did I deliver and what I could do differently? So that's been really important for me.

When I think of building a new institution, I have a lot of experience to bring forward. And of course, you can rest assured that I wouldn't do it as a counter-position. For instance, now I'm a chair of an arts charity New Contemporaries, and I have been really building a different practice of a board culture there. And that is not controversial or contrary to my experience. It is a different way of being a chair and supporting an institution.

Charlotte Burns: That's so interesting. Thank you for being so open about that.

Fatoş Üstek: It's important to be open. I think we don't talk about these things as much.

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: People in museums are talking. But are we listening?

Major institutional directors are increasingly sounding an alarm. Here's Glenn [D.] Lowry, the director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and a guest on season one of this podcast.

[Excerpt from Glenn Lowry speaking on a panel at Talking Galleries]

Glenn Lowry: The key to the success of our cultural ecosystem, and here I mean it writ large, could be at risk.

Charlotte Burns: Glenn is talking here on a panel at Talking Galleries conference, which was organized in partnership with Schwartzman& in New York, in April. Asked if there are political events on the horizon that could shake the system, here's what Glenn said:

Glenn Lowry: Absolutely. I mean, we saw in the fall what happened to higher education when Congress went after three remarkable leaders, who all happened to be women, who all happened to be in the first year of their tenure. You can say it was an ambush but the consequence of it is a congressional focus on whether or not higher ed is, quote, “performing,” as it should. And antisemitism may be the trigger, but once you start unraveling that, the next step is to look at whether or not those institutions deserve the tax benefits that they do. Well, they're the same tax benefits that museums, and symphonies, and orchestras have. And those benefits have been reduced in the past under [former President Ronald] Reagan. They were then restored because there was an outcry. But they're not a tablet from Moses that says they're a given. So I actually think that it is not impossible that in the relatively short term, there could be a real attack on whether or not the not-for-profit organizations in this country, except for religious ones, deserve the tax benefits that they have.

So what's the result of that? They could be removed. They could be diminished. Either one of those creates havoc. Some museums will survive that, the vast majority will not. And it would be a travesty because this country has built the most extraordinary ecosystem of cultural institutions in the world and it did it in very short order. And the trigger to that was a change in the tax code.

You look across this country, what we have is astounding. So, I worry a lot that without thinking about it, in an effort to kind of punish people, institutions, the whole system can get unraveled.

Charlotte Burns: Glenn is not the only leader talking in plain terms. Jessica Morgan, the director of the Dia Art Foundation, and one of our guests this season, recently said: "We’re witnessing a broad-scale backlash…and it is disproportionately taking down women." Talking to me for an article for Art Basel on International Women's Day, Jessica said: "There is more fearfulness about putting your neck out…because, when things head south, the forces are so strong they can quickly take people down.”

This is serious stuff. These are major leaders saying that they feel museums may not survive. That cultural leaders and organizations are under attack. This isn’t paranoia. It's happening.

In the US over the past eight years, rights for women have been rolled back, with the overturning of major laws like Roe v. Wade. A female President feels like a pipe dream. The art world might like to see itself as a progressive outlier but it’s not. There is not gender parity in museum collections or displays—progress peaked in 2009. Nor is there parity in the market, nor in the workforce.

It’s a silent crisis that since 2017 almost 40 senior female museum staff, mainly directors and chief curators, have left their positions, mostly in the US. But rather than being looked at as an industry problem, these departures are treated as one-offs. Of course, every story is different. But still.

This came up in my conversation with Mia. She said she’d been reading the writer Sarah Ahmed.

[Excerpt from interview with Mia Locks]

Mia Locks: There's a couple of great phrases from her work that resonate with what you're describing about a number of us women having been through something in an institution and moving through it. I feel like the common thread is, when you expose a problem, you pose a problem. And there's a way in which once you've exposed an issue or an inequity that's happening, you, yeah, you sort of are like, oh, the person that maybe created that problem. And suddenly that reveals something about the system. And sometimes people don't want to hear that. Or sometimes the room isn't prepared to grapple with it.

I don't have any expertise in this, but I guess I can just speak personally. One of the things I've noticed is that when you go through some sort of difficult moment or when you're forced into a position that you weren't prepared to be in, or when you're frankly harmed by an institution—we hear about this a lot—a couple of things happen. Suddenly you really redefine what's important to you. That can, I think, increase a lot of your commitment to personal mission, which for sure has been the case for me. But the other thing that happens is this kind of increased bonding, or you seek out networks of support and others with shared experiences and you collectively revise your priorities. There is this sense that nobody wants to feel like what they experience is for nothing. What is it that we could do together to make sure that these things don't happen again? And what are some ways that we can support those that are trying to shift dynamics so history doesn't repeat itself?

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: What if we can learn from history? What if we can figure out how to do things together differently? I mean, that's the kind of stuff we talk about within museums, so how about we listen to the swell of voices inside them at every level asking us to pay attention? This is a tough time for cultural institutions. Their future is not guaranteed. But there are a lot of people working hard to figure out solutions.

Here's Mia with more on Museums Moving Forward, which came about when dozens of museum workers got together.

[Excerpt from interview with Mia Locks]

Mia Locks: One of the key questions we kept asking ourselves was, “Are these problems and issues that we're finding ourselves in the midst of specific to us as individuals, are they about our specific institutions, or are we really dealing with a structural issue?” We were also asking ourselves, “Okay, so let's assume our hypothesis is that museums as workplaces have not developed at the pace of all kinds of other sort of movement in the field. How might we even begin to tackle something that complex?” So we actually designed a quantitative data study that could help us bring some numbers to the things that we were seeing and experiencing ourselves. We released our first data study report in October of 2023.

Charlotte Burns: The report was called Workplace Equity and Organizational Culture in US Art Museums and of the 1,900 museums staffers surveyed based at 54 US arts-focused institutions—so it's a really broad-based participation—74% reported an inability to cover the cost of living; 68% of those surveyed had considered leaving the field. So these were quite damning findings, reflecting a real discontent, which you sort of knew but this really named.

Mia Locks: I guess it could be seen as damning, but I think for anybody who has worked in a museum for more than, I don't know, a few months, I don't think any of this was surprising. And actually, we heard that from a lot of people; nothing actually really shocked people. There were a few things people were like, “Oh, that's actually the number kind of helps.” But nobody was “Wow, workers in museums are unhappy?!”

But, for us, it was still important to bring some of those numbers, to synthesize them in the format of a report, which is ultimately a tool. What we were hearing from people in leadership positions was, “Yes, I know, but actually, it's really hard to have these conversations because without actual numbers, it's really hard to a) advocate for change and b) to measure if we are indeed changing.” So, developing a tool felt really important.

Look, I mean, Charlotte, you and I know this, but it's not like I'm naive about the fact that museums are facing a whole host of issues. But I do think we also know that it's not sustainable to continue as a field if we're not going to take much more seriously these questions about what's happening in the workplace. The report needs to be at the table as leaders are making decisions about their strategic plans, their budgets, or their operational plans.

Charlotte Burns: Museums Moving Forward is an independent, limited-life organization devoted to not only envisioning but also creating a more just museum sector by 2030. So it's a really ambitious organization: it's not here forever and ever. That's a big ‘what if;’ what if you could create within a short space of time a better work environment, a more just sector. How do you go about creating that?

Mia Locks: We'll do a report every two years. You can't just look at a single data set. Of course, you want to be looking at longitudinal data. You want to be able to say, “Here's what's changing. Here's what isn't.” And then in between, we're gathering really critical and complimentary qualitative data. And we do that in convenings or gatherings where we bring folks together across departments, institutions, cities, regions, to actually roll up their sleeves and sharpen their pencils and co-design solutions, but grounded in the data and really focused on what would be a different way of thinking about this.

It's classic workshopping experimentation that, in my experience, doesn't happen a lot inside the museum for a whole host of reasons. And our mission is designed to fill that gap.

Charlotte Burns: When we were having a conversation preparing for this, you were saying that one of the really heartening things was that kind of coalition of the willing that you've been able to build. That there are people that really want this to happen. You're not banging your head against a brick wall. You are finding lots and lots of partners who very much want this change, very much are happy that there is an organization trying to find these solutions, and want to support this work.

Tell me a little bit more about that, because I think we don't often hear that side of things.

Mia Locks: Yeah. I guess that has been somewhat surprising. As we've started to gather again, after the report, we've given a lot of talks and we've been in conversation with a whole host of stakeholders across the field, across the country. And at every turn, literally, we are hearing that the vast majority of our sector really does want to see this kind of change. I think people really do believe that the museum workforce needs to be more diverse by every metric and that museum leadership needs to be more diverse. For sure that's something I believe. I think that's something you believe. I think we've talked about that a lot on this podcast, but I really do believe that the overwhelming majority of the field has alignment on that.

And it feels somewhat rare to me that there be that much alignment on something. There's so many ways in which the art world splinters and doesn't agree but I really do think the vast majority of us want to see that happen. The rub, or where the rubber meets the road, as they say, is exactly how do we get there? What's the time frame for that? And ultimately, how do we prioritize that when these museums have other missions?

Most museums, nowhere in their mission does it say, “And we're trying to be the best workplaces out there,” or that, “We're committed to improving the lives and conditions of our workers,” like that's not their mission. That's our mission. And the reason we're limited life in large part is because if we're successful, we shouldn't have to exist anymore, that this will somehow get embedded into institutions because the data will show—and I think it already does, but hopefully in a long-term way, we'll demonstrate—that the dominant organizational structure of museums is not sustainable. That if we as a field can't figure out a way to have culture workers thrive because of their commitment to art and culture instead of in spite of it, then we're going to continue to see the fracturing, the frustrations, the protests, the kind of dissolution of trust in our institutions.

I'm hopeful that we can agree on that longer-term goal and I'm hopeful that Museums Moving Forward can help provide tools that will get us there as well as some recommendations we could try both in separate institutions, but together as a field.

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: So Mia is optimistic about the field. It's a helpful reminder of how much change can actually happen in a relatively short period of time. The crises we face aren't new. In the cultural field in America, we're almost a decade into this specific political period. Re-reading Laura's book took me straight back to 2016 and the early, chaotic days of the Trump presidency. The book captures the surging force of a new kind of political reality and its immediate impact on the Queens Museum.

Around 5% of the staff were impacted by the Trump admin's promise to revoke Obama's [DACA] Dreamers program, which gives protection to undocumented immigrants brought to the US unlawfully as children. This set off immense panic and fear in communities around America, including the Queens Museum. Then, shortly after the museum was in the headlines again, the board had decided against hosting a political event only to reinstate it after media backlash. Then during the event, Vice President Mike Pence announced a key piece of policy, dragging the institution further into national politics and national tabloids.

Here’s more from my interview with Laura.

[Excerpt from interview with Laura Raicovich]

Charlotte Burns: So there's a presidential election, it immediately impacts your staff, and you're dealing with that as the director navigating between the staff impact and how to move forward as an institution and explaining your decisions to the board. Then that quickly moves to you, there's another decision made about an event at the institution. You explain your decision to the board, the board agrees. There's a backlash that comes out in the press and it escalates, it becomes very political. The vice president comes to speak, you're accused of antisemitism. Your husband counsels you to talk publicly about his family's history, including how his grandparents were Auschwitz survivors, and you write: “It felt horrible to trot out facts about my existence in the effort to convince people who'd known me for years that I did not hate people for their cultural or religious backgrounds.”

As a reader, you feel this swirling sense of escalation that there is a political event and then you as a director, the circumstances unfold, enveloping first your staff and then you. It's just this escalation that's really beyond anything you could control, and then by January 2018, you write that knowing a group of board members was unhappy with you and decisions you'd made as a director, you made the decision to resign.

You also write about things that other museums were doing, the [Solomon R.] Guggenheim, MoMA, and immediately took actions in defiance of this promise to revoke Obama's executive order. And I was thinking, “Gosh, I'm not sure that institutions would move so quickly now on things like that.” It feels further away actually that museums would take such swift action politically in 2024 than it did in 2016. That felt like uncharted territory and it felt like the beginning of a new moment. But that new moment now is not so new.

Laura Raicovich: The Queens Museum is a very special place in part because especially when you're talking about issues of immigration, migration, and precarities related to those conditions, these are not abstractions. It's about how a change in policy actually is unfolding in real-time in people's lives. This wasn't about taking a political stance because it sounds good in a public statement. This was about recognizing that the people who I worked with every day, some of them were under an enormous amount of stress and they were swept up in this, the chaos of the entry of the Trump administration, and they were in free fall. As a human being, I just felt like I wanted to support them in some way. And I felt that the museum, as their employer and as an institution that had devoted itself to working with immigrants since far before I got there, and that had been a very much a point of pride, should actually restate those values and actually act on them.

And just to be clear, it wasn't necessarily that the board didn't believe that, but some of them did not want it to be quite as public as I thought it needed to be. We have to remember that in that particular moment, there were literally people living in Corona—which is the neighborhood just surrounding the museum—that might have even had documents, and for fear of ICE sweeping them off the street, people, if they left their homes or going one at a time.

This wasn't an abstraction. So I felt a real obligation to engage with that in some way. It didn't occur to me not to, and I guess, what's changed between then and now is that moment hasn't left us, right? These are conditions that we are now living with for an extended period and we are now facing an even more conservative turn in the culture at large. But I also think that there are many popular movements and things that make me have hope about the change that might eventually come. There's that gripping onto power that often happens in the face of very real change.

Charlotte Burns: Laura, what you said then about moving into a more conservative moment echoes something that leaders in institutions were saying to me recently that they fear that there is a backlash brewing. What if you were a board member who wanted to better support your leaders? How could you do that?

Laura Raicovich: It would depend on what institution we were talking about because it's very different to talk about a place like the Met[ropolitan Museum of Art] or the Whitney [Museum of American Art] or The Laundromat Project, but the work has to happen on multiple levels. There have to be shifts within the operational structure in order to operate the values of the institution. Actually paying attention to how things are being done as well as what is being done.

In these moments, we need to have the courage to not shrink away from the tough discussions. And I mean that both from a governance stance and from a content stance. There are a lot of tough conversations that need to be had now and I think they should happen. How they happen and in what context and who's in the room and how that all unfolds, that is something that is a strategic question and a tactical question. All of those things need to be considered. But to stop moving the conversations in the direction we know they need to go would be a mistake, especially during this period.

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: Who wants to be a museum director these days anyway? According to each of our guests, the role is ripe for a revamp. Having once never imagined a career outside the institution—Laura can't now imagine being a museum director ever again.

[Excerpt from interview with Laura Raicovich]

Laura Raicovich: It's just an absurd balance with the consolidation of wealth and power being so collapsed into the board space and the gap between the life experiences of what a typical board member experiences on their day-to-day of an institution, say, like the Whitney Museum and a staff member. That's a very big gap to negotiate all the time and it's only growing; it's grown even since the pandemic.

These are much bigger questions of how society is moving in a more consolidated way towards many fewer people having an even vaster relationship to the wealth that exists in the world. These are social and economic conditions that far exceed the museum but the museum is a perfect mirror of them. And to me, the museum is a very useful space to experiment in these kinds of ways, because it so closely mirrors that of society that we can hope to perhaps learn something from it if we can succeed in reorganizing things.

Charlotte Burns: So what if you were designing the institution of today and tomorrow? What would you do knowing the problems from the inside out? Can they be fixed?

Laura Raicovich: Different kinds of institutions can be fixed to various degrees. You have so many different kinds of players within it, so the expectations can't all be the same, right? However, one of the primary problems with cultural spaces is their dedication to the leadership models of late capitalism and I call this the ‘Marlboro Man’ problem. If you think back to those ads from the 1970s, which are so iconic for the Cold War era, I feel like you see this kind of cowboy rugged in the sunset on his horse, smoking a cigarette, and it's the kind of very American, self-sufficient individualism that is such an enormous mythology within our leadership structures.

And so one of the things that I think could be really useful is understanding and reenvisioning the museum as a profoundly collective endeavor—which it clearly is, given the number of people that it takes inside of museums to actually make stuff happen on the day to day—and dispense with this idea that the director or the curator is this lone, brilliant, visionary individual that's making it all happen because that's, in fact, probably very useful from a fundraising perspective, but not necessarily very useful in an institution-building perspective.

Charlotte Burns: Mia also thinks that shared leadership is the way forward.

[Excerpt from interview with Mia Locks]

Charlotte Burns: Do you mean specifically then the title?

Mia Locks: I think all if we can try it in all the ways. It's not something that could happen tomorrow, but I have heard rumblings from folks that sit on search committees, there's an interest and a curiosity about that, probably a bit of fear, trying something new. Especially a high-stakes move like at the kind of executive level, it'll certainly be scrutinized and I don't think any museum leader is looking for more scrutiny right now. But I think ultimately, yeah, I'd like to see us experiment a little more with that. That kind of lone-wolf leadership model doesn't work anymore. I think people know that but they don't know how to get out of it.

Charlotte Burns: Fatoş has written a book called The Art Institution of Tomorrow, which pitches a different kind of the leadership model.

[Excerpt from interview with Fatoş Üstek]

Charlotte Burns: Your opening lines for this book, I love, I'm going to quote you. You say: “The world is in crisis, seeking a new direction in which to evolve with meaning and integrity, although it often does not seem this way. On the contrary, it may at first appear as if we're heading in precisely the opposite direction, where our experiences are hollow and communities divided.”

I thought there was such great summation of where we are right now, this search for meaning and yet a sort of lack of ability to get there. Your book is an attempt to envision a new model.

Fatoş Üstek: It is so significant to bring a wider perspective to what's happening in the world before we talk about the specificity of art institutions and their role. Art institutions are stagnating. We live in a society that is unlike any other. The concept of locality is different. There's also the change in the arts. The art itself and the artistic practices are changing. And exhibition making, the traditions and histories of exhibition making are due to have a change. Artworks don't want to be only stable. There are shifts happening in a continuum at a faster pace in the 21st century than ever before. And institutions are not really equipped to respond to these crises in a meaningful, very informed manner. What happens then is the outcome is reactive programming, or very short-term solution-making that does not necessarily address or revise the underlying inherent structures.

Charlotte Burns: One of the things you talk about that I thought was really interesting was this kind of competition in the art world that you define as unhealthy. You talk about small steps taken towards cooperation, but say the art sector is still very disjointed, exclusive, and competitive. How do you address that? What if the art world were less competitive? How would that work? What would that look like?

Fatoş Üstek: Big tech conglomerates now use this methodology of embedding distributed intelligence within their organizations. Organizations can restructure themselves, their operations, in order to make the most of this distributed intelligence that is brought in by every specific person in the team. The same methodology could be applied in a different scale, in an external scale, where a distributed intelligence can be formed among the institutions that are taking part in a local, national, or an international context. That means perhaps we don't need to deliver on all fronts as a single institution but we share knowledges, we share skills and we share our methodologies of overcoming hardships or trainings, learnings, that we have developed through our experiences. Because even though institutions might be going through the same crisis, they're going at it at a different scale and at a different impact. So that would be my antidote to the problem that we are facing right now.

Charlotte Burns: When you say you want to think about shifting the institution, do you want to shift it? Do you want to build something new? Do you think it's possible to change it as it stands?

Fatoş Üstek: So my ambition is actually to really start this new institution from scratch, but I also don't want to be the only director of that institution. I think the future is really built on decentralized forms of knowledge production and sharing of that knowledge and skills. I think it's really about everyone in the organization being a sensor for the organization, not only the ‘genius director’ that is set on top, or the boards. So, yes, the ambition is really to start one. And one of the core things that needs to be tackled is decision-making, how decisions are made in the organization, and who makes the call. Perhaps that needs to be decentralized.

Museums were the drivers of visual culture and now visual arts and performing arts are only a subset of a wider domain of visual culture that is foiled by the advancement of technology. So how do we then step outside of that old cloak of being a cultural authority, or being the centers of discourse and validation, to being parts of that global culture that is actually produced at different scales by everyone that's part of that global society?

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: Ultimately, this is about the value of art and culture, and what they mean to us. What do we think museums are for and what do we think they can do? How do we then pay for them? That brings us to money, which is also often about power. New kinds of thinking are required.

Laura has one proposal. Together with Laura Hanna, she recently wrote a guest essay in The New York Times called “To Save Museums, Treat Them Like Highways". It looks at cultural infrastructure and spending in the United States on a national level, via governmental infrastructure bills. It's a rebalancing, she says, so that the public has more of a stake in what happens inside cultural spaces and so that we have the opportunity to have more of a public conversation about culture and what it means.

[Excerpt from interview with Laura Raicovich]

Laura Raicovich: What is culture and how is it mobilized in our daily lives? There is something very profound that we need to talk about around what the difference is between what happens in museum space, in community space. What happens in a bar is culture—and I say that very knowingly because I've recently opened a bar in the East Village that also functions as a cultural space. How do we begin to rethink what, in our imaginations, culture might look like?

Charlotte Burns: I really loved the op-ed; it gets to this issue of how we treat art, and brings it quite back down to earth and, says, no, it's just part of life and we need to start treating and funding museums, theaters, and galleries less like sacred spaces, less like these rarefied things and more like interstate highways, the internet, and use money that's earmarked to maintain the country's infrastructure.

You provide a pathway to lobbying, essentially, for bringing federal funding into the arts via infrastructure bills. Can you tell me more about where any of those initiatives are going?

Laura Raicovich: Yeah. The op-ed is basically the very first shot over the bow, I think the expression is, to basically begin a conversation about what this might look like. I have been thinking about cultural infrastructure as a question of equity for a very long time and cultural infrastructure is not only the physical buildings and deferred maintenance and other kinds of physical matters but it's also people. If you don't pay people to open the doors and clean the toilets and do all of those things, but also to actually put the work on view or work with the artists to make the production or record the music, you don't have culture. That's why we call them culture workers because they produce the culture with the artists. And this is an important point, especially in the US, because if you don't have a full-time job, it's very challenging to get health insurance. And so culture work would be wrapped up as a form of infrastructure that would not only provide the literal tools to actually make culture, but also provide a massive amount of fuel for the economy.

The economic development argument that has been used for a very long time in the US has been, if you have a museum in your town, it will bring tourism and other things. And yes, it will employ people and all of that but the focus has really been on bringing people from outside that area to spend money there. That is important. But I also think paying people a living wage to do the work near where they live to get health insurance, you're creating a level of stability. Never mind the fact that in the US I think…I don't remember the figure…

Charlotte Burns: We have it here. Culture in the US employs about five million people and pumps about $1 trillion into the economy annually.

Laura Raicovich: So that $1 trillion number of economic impact is enormous. That's a big industry when you compare it to other industries in the US and it's also spread very unevenly over the US. It’s a very large nation, obviously, and there is so much more that could be developed across the nation.

So, all of these economic realities really affect how people understand what culture is and where it's physically located. And so this reexamination is about really thinking about what is culture? And what if we thought about culture in a radically different way? How would we feel about funding it, as a society? And if it included, perhaps, the line dancing at the bar in the West, that whatever is a popular thing for people to do on a Wednesday night that's not in a big city or whatever, that's an important piece of the puzzle.

Charlotte Burns: It's additive rather than oppositional. People tend to get stuck when we have conversations about funding. And you say here, “It would help disentangle larger arts institutions from the largess of wealthy individuals and corporations,” and it would, “defang” some of the culture war arguments because it's harder to object to paying to fix a leaky roof than to paying to exhibit a photograph.

Laura Raicovich: And I guess I would also point out that it's a very tiny percentage of these enormous bills would make an incredible impact on the cultural world. What we're talking about in the kind of many trillions of dollars that is allocated towards infrastructure is that a teensy piece, a half of 1%, half of a percent, would change the landscape. And so it all of a sudden doesn't seem like such a big ask. Or maybe? I hope!

So the idea now is to really work out how do we now find the right people who can help advance this idea. And I'm working with Laura Hanna, who is my co-author on the piece, to actually begin to map those next steps.

And, obviously, these are long campaigns to be thought of in years, not months. But this is the beginning. And so I hope that we begin to lever open some of these spaces for conversation and discussion about how government works, could work, doesn't work, and figure out how to take those next steps to make something shift. And undoubtedly, the idea will change over time because what do I know about federal funding earmarks and all of that.

Charlotte Burns: That's really fascinating. But it seems very pragmatic. You say here in 2021 in a bipartisan bill, the federal government allocated $1.2 trillion to national infrastructure projects over five years. And this isn't even 0.5% of those funds, which would be $6 billion or $1.2 billion annually.

Laura Raicovich: The NEA, which is the National Endowments for the Arts, which is the good housekeeping seal of approval, if you will, I think that they give out about $250 million a year. Just as a comparison to the $1.2 billion. It would change the game.

Charlotte Burns: What was the reaction to the piece?

Laura Raicovich: Overwhelmingly positive. I would say that there's a lot of work to do on understanding what the realities of attempting to go forward with this are and that was pointed out by several people, who are very much in the know, whose work I respect. And I do feel like this is a way of putting a big idea out into the world so that other people can begin thinking about it as well. This isn't something that Laura and I are going to do on our own. It's going to require a massive network of people who believe that we can make this kind of shift in the United States. And to envision how it might work. As I say, it's a very beginning first step.

Charlotte Burns: Bravo on taking a first step.

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: The real power in American museums are the boards, which fund the institutions and are responsible for their well-being at every level. We’ve heard a new funding proposal from Laura. Mia and Fatoş are also experimenting with the existing model.

[Excerpt from interview with Mia Locks]

Charlotte Burns: What if governance were different? What are your recommendations in terms of leadership, in terms of ultimate authority? Which is the board composition?

Mia Locks: That's probably the toughest one. It's so much easier for me to say this because we're a new organization, but we've structured ourselves in a way that separates the governance from the fundraising. Our board is made up entirely of museum workers because we're focused on the workplace. The expertise of what's happening in museum workplaces, I think we can agree, comes from the people that work in them. And we have a separate group called our Vision Council that we're building. It's basically a nationwide network of philanthropists and other art supporters who see the value of what we're doing. Maybe they're already on a board or they don't need to be on our board. And that's not even the invitation. The invitation is to support the opportunity for somebody else to sit on our board and in some cases, maybe it's their first time on a board. So they're learning really hands-on skills about being on a board.

A number of our stakeholders pretty early on in our convenings in 2021, when we asked them, many of them were getting interviewed for the first time or getting brought into these searches for leadership positions, more management positions, some of them, director positions. And so many of them—and I will just say almost exclusively women, and a majority of them women of color—said to us, “We get into those rooms, we're on these lists, we're invited to present some ideas, and then we're ultimately told, “But you don't have enough board experience. You need board experience, but we can't give it to you, but you need to figure it out or you can't get to this next level.” And we thought, that's something we could do. So why don't we develop a board that is effectively a kind of professional development opportunity, so that people in museums could actually learn about what it means to be on a board?

So that's one of the ways that I see, for our work, a really critical difference, which is to say the people that support us don't need to be our governors. The people that support us because they believe in the mission. And I wonder sometimes if other organizations could think that way.

But it's much easier to build a new thing than it is to fix an old one. So, that's not lost on me. But because we were in this nascent moment thinking about all these things and asking ourselves these questions, we thought, “Actually, let's structure it this way so that our board of stakeholders are the sole governors and that the philanthropists and others that support us are a different group.” And of course, there's overlap and of course, they connect, and of course we gather together to talk about these broader issues. But to us, that separation between governance and fundraising felt like one way we could experiment with the model as it exists.

Charlotte Burns: Fatoş also suggests a new governance model.

[Excerpt from interview with Fatoş Üstek]

Fatoş Üstek: Yeah, I am suggesting a radical systemic change because it is really about employing a different mindset. The hierarchical pyramidic models of organizational structure has come to an end, that model we inherited from the birth of the museums.

However, in today's accelerating society, we need institutions to be able to respond and engage in the same pace. Something that has been really blocking the institutional ability and agility is the bureaucratic systems that are set in place. So, in this new model, the boards and the governance bodies and advisory boards and stakeholders and benefactors don't have hierarchies that are built on the status of dominance. There are certain processes that are obstructions to be attentive to change, to be spontaneous where it is needed.

What I am suggesting is that boards, instead of separating themselves as the strategy and vision and overall decision-making structure, really integrate their work with the team so there's more of a porous collaborative ethos instead of these stratifications of who holds the knowledge of the institution and who makes the decisions for its future.

Charlotte Burns: And how does that process work? Because I can already hear half the art world saying, “Ugh, you can't make decisions by committee. We don't have time for a million conversations.” How does that work?

Fatoş Üstek: We actually need to demolish departments. Instead of departments and heads of departments, we actually need to build cross-skilled teams and those will also need to be skilled in self-management and conflict resolution.

My ideal institution that I'm sketching right now is composed of five teams: experienced fundraisers and newly starting up curators, or marketing people or communications or systems coders. Different people with different mindsets and skill sets. They could work together to deliver a project.

Charlotte Burns: So, you're sketching out your ideal institution. How are you going to fund it?

Fatoş Üstek: Again, it's going to be decentralized. But also non-hierarchical. There are multiple hierarchies that we operate within the art sector and those hierarchies look really healthy and sustainable, but they have been coming with strings attached. My main goal of thinking about a business model for art institutions is how to make institutions more autonomous. How could we delegate agency and autonomy in an institution where the business model is supportive of that?

I think, as society, we perhaps need to change our understanding and perception of art institutions, that they are here to contribute towards the expansion and a wealth of culture. And maybe that is where we could connect with them and build a much more non-hierarchical support.

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: While Fatoş wants to make something totally new, Mia hasn't given up on the museum just yet. The only way through is...through.

[Excerpt from interview with Mia Locks]

Charlotte Burns: What if you were thinking of museums now? Could you imagine yourself going back into a museum? Could you see yourself wanting that life?

Mia Locks: Absolutely. I think I'm interested in going back into museums. My question is whether museums are actually interested in people like me being inside of them. That's actually a question I can't answer.

But yeah, I still really believe in museums. There's a lot of people out there that don't and say we can't with the old models, we’ve got to invent new things. And I think we need that too, but I'm not personally willing to let go of this idea that these institutions can change, that historically they have served a certain purpose and they've been structured a certain way, but that ultimately they're still doing something that I value, which is showing art and holding onto objects that tell us something about who we are now, but also hundreds of years from now. So that people could know what mattered to us and what we were thinking about and talking about. So I guess in a very romantic, with a capital ‘R,’ way, I still really believe that. So of course I would absolutely love to help the field figure this out from the inside.

But at this particular moment, I think most people are afraid to step into that role because they know the public scrutiny is so real, that the standards are so high, that the kind of stakes of the game are just intense, but yeah, I guess maybe I'm less afraid of that having been through it, but also I just don't think there's any way through, but through. I just don't see us avoiding this wholeheartedly and powering on. We can temporarily delay. We can take our time with our priorities, but at the end of the day, these institutions are going to have to change if they're going to survive. And I think everybody knows that.

So yeah, I would love to, of course, be part of that change. I just don't know how much the existing structure is really ready to, like, kick into gear and how much we're still evaluating and assessing our next steps. But, yeah, I'm in it for the long haul, if you will.

[Musical interlude]

[Excerpt from interview with Fatoş Üstek]

Charlotte Burns: So I'm going to ask you two questions. What is the ‘what if’ that keeps you up at night? And what is the ‘what if’ that gets you out of bed in the morning?

Fatoş Üstek: I think I'm an optimist in general. I was thinking about this question because I knew it was going to come. So my ‘what if’ is, what if it all works out? So that keeps me up at night and gets me up in the morning.

Charlotte Burns: I love that.

[Excerpt from interview with Mia Locks]

Mia Locks: I actually don't let things keep me up at night anymore. That's like the gift of getting older. I don't let that happen. It's not worth your health. That said, I do wake up each morning pretty motivated to figure out how we can prepare museums to really embrace the change that we're in because I think if we don't, I am really scared that they're going to close. We already know that there's all kinds of structural deficits that it's already quite expensive and challenging to run a museum. But if we can't solve this broader issue about how to be better workplaces that we are ultimately going to see museums fail. And that breaks my heart. I don't want them to go away. I don't want people to not have access to them. But I do think if we can't find a path forward, that we are going to see that. And that definitely motivates me to help prevent that from happening.

[Excerpt from interview with Laura Raicovich]

Charlotte Burns: Laura, what's the ‘what if’ that keeps you up at night?

Laura Raicovich: What if Trump gets elected again? [Laughs]

I shouldn't be laughing when I say that, but, oh dear! I'm worried about that one.

The global slide towards authoritarian leadership seems to be happening in all corners. And I think there is this grand mythology that the United States is somehow magically resistant to that, but it clearly is not. But I guess that's a piece of why I think the cultural aspect of making change is so necessary because if we can't imagine how we want to live and the world we want to live in, how can we possibly make it happen?

And I always go back to this Karl Rove quote, he said this during Bush's administration. He said, we're creating reality right now. Everybody else is just reacting to it. And this is where I think the right has actually made enormous strides. They've constructed this reality. This is the violence that's being perpetrated, is a violence in our imaginations, which is, in the end, why I think culture matters.

Charlotte Burns: Laura, what's the ‘what if’ that gets you out of bed in the morning?

Laura Raicovich: What if we could create that, as my friend Jonas Staal says, emancipatory propaganda, that elusive story. Remake that story into a narrative that is not about consolidating wealth and power and influence, but mutual liberation. That may sound like a utopian idea, but that is what gets me out of bed in the morning.

Charlotte Burns: What's wrong with utopia?

Laura Raicovich: That's another podcast. [Laughter]

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: Thank you to our guests Mia Locks, Laura Raicovich, and Fatoş Üstek. Thank you so much for taking part.

We’re heading to the end of the season. Join us next time for our editorial advisor roundup. But we have some bonus episodes coming up too. More details on that next time on The Art World: What If…?!

This podcast is brought to you by Art&, the editorial platform created by Schwartzman&. The executive producer is Allan Schwartzman, who co-hosts the show together with me, Charlotte Burns of Studio Burns, which produces the series.

Follow the show on social media at @artand_media.