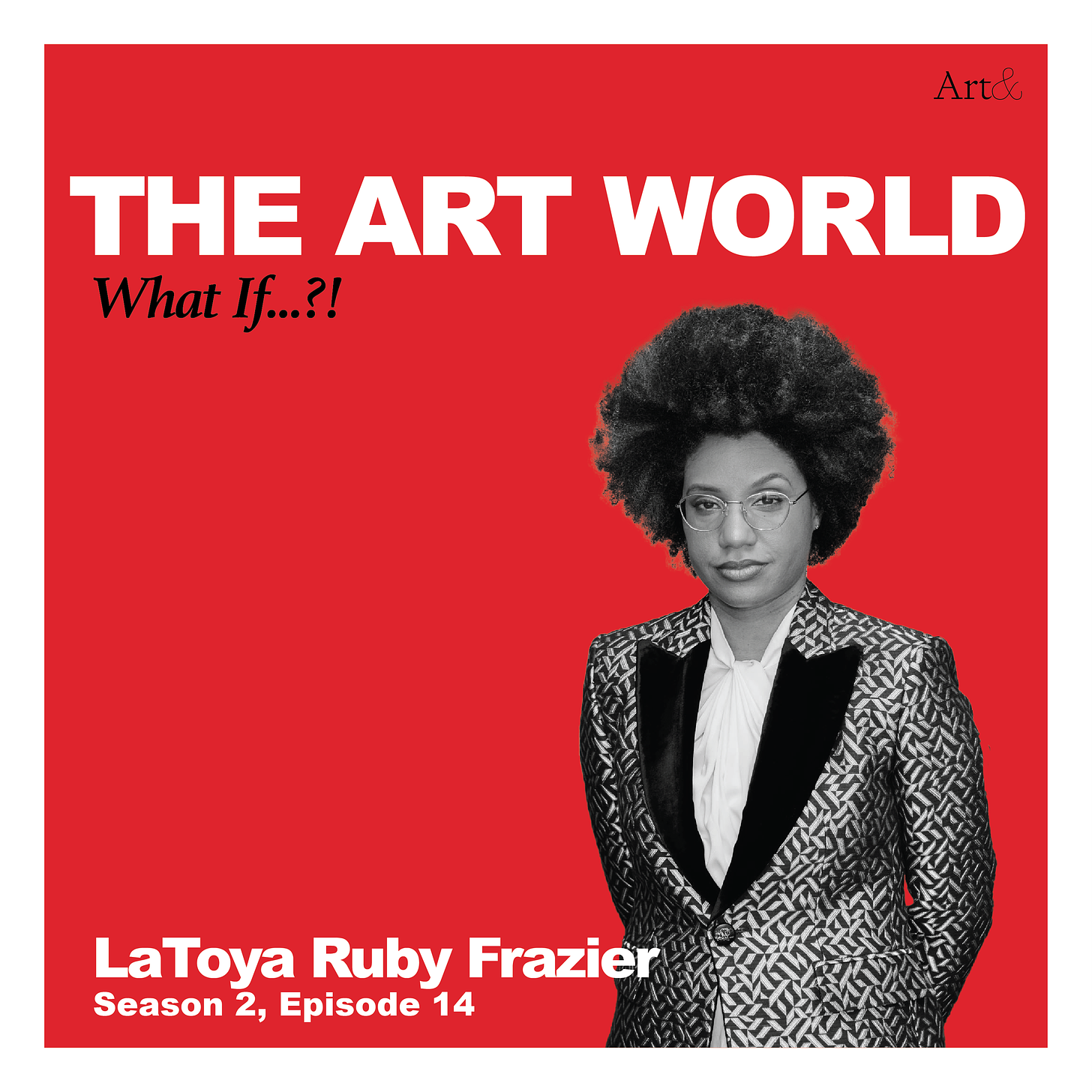

Photography by Sean Eaton. Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art

This time, we’re joined by the artist LaToya Ruby Frazier, just before the opening of her major new exhibition Monuments of Solidarity at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “This exhibition spiritually uplifts people,” she says. “It inspires people to be the change they need, but it also inspires them to be better human beings. To look beyond the self to look beyond individualistic desires to think about the fact that you are connected to an ecosystem and a world around you. People won't be the same. This is a transformative exhibition.” We delve into LaToya’s faith and the impact of art on our lives, its power not only to shine light into the darkness but to move through people and communities and so to create profound, lasting change. Enjoy.

Charlotte Burns: Hello and welcome to The Art World: What If…?!, the podcast in which we imagine new futures. I’m your host Charlotte Burns.

[Audio of guests]

This time, we’re joined by the artist LaToya Ruby Frazier just before the opening of her major new exhibition Monuments of Solidarity at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: “This exhibition spiritually uplifts people. It inspires people to be the change they need, but it also inspires them to be better human beings, to look beyond the self, to look beyond individualistic desires, to think about the fact that you are connected to an ecosystem and a world around you. People won't be the same. This is a transformative exhibition.”

LaToya is an amazing artist and this is such a great conversation. We delve into her faith and the impact of art on our lives, its power not only to shine light into the darkness but to move through people and communities and so to create profound, lasting change.

I really hope you enjoy listening to LaToya as much as I did talking to her. Let’s begin.

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: Thank you so much for making this time to be with us, LaToya. It is so great to be able to talk to you.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Charlotte, it's my pleasure to join your program.

Charlotte Burns: Especially because you are so busy. You're in the middle of your install for this MoMA show. I imagine time is a sort of precious commodity more than ever right now. How is it going?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: It's going really smooth. It's going really well. It's just a lot of work because it's 10,000 square feet, nine massive rooms, really immersive photographic installations that become quite sculptural, and there's also multiple sound components. It's a lot to install, but we are moving along pretty swiftly and it's really taking shape.

Charlotte Burns: So this exhibition, LaToya Ruby Frazier: Monuments of Solidarity, it's your first major museum survey in the US. You've reimagined 10 bodies of work as a sequence of immersive installations that are monuments for workers' thoughts.

You said something a few years ago that you want to establish a museum of workers’ thoughts. An institution aimed at fostering solidarity among working-class people around the world where you would teach and you'd maintain your archives. And you told the [New York] Times, “Maybe I could see it happening before I die. Maybe I could help plant that seed.”

So is this show part of planting the seeds for the museum that you want to create?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Yes. This exhibition is absolutely the inception, the beginning of that invitation to really invoke and also bring into existence this institution that I do believe will transcend all the things that are holding us back as a society in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, citizenship, and religion. It's hard to do that without having a real visual aid.

And so this exhibition, unexpectedly [Laughs]...because the way it happened, I was at the photographer's forum where Roxana [Marcoci] has those contemporary art conversations. And I was talking about [LaToya Ruby Frazier:] The Last Cruze and it being a workers’ monument and just requesting that it would be beautiful if it were here at the Museum of Modern Art.

And so, I believe I spoke it into existence without realizing it until I actually started to work on the show these past several months. It only dawned on me as we began to get through the catalogue and start to lay out the show that this actually is the idea that I proposed at the end of that New York Times article about a museum of workers thought.

So it's really here at the Museum of Modern Art where it's taking shape and coming into existence. And I see it as a springboard for me being able to actually launch the type of cultural center that I would like to after this exhibition.

Charlotte Burns: As you're working on the show thinking about that springboard, what are the things that it's shaping in your mind? Where do you start seeing things take more concrete shape?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: I'm of two mindsets at the moment. One thing is I do have this belief that people are walking institutions. It's about the energy and the care and the knowledge that we put into each other and that we reflect in each other. Oftentimes as artists, we're being pressured to have a brick and mortar, to have boards, to become very institutionalized ourselves and I'm concerned about that.

I think that we are extremely institutionalized as a society, and the only way to really get through and to help transform people through art—for me, over the past 25 years of my practice, it has been in the most intimate, personal spaces and ways. For example, when I'm in families’ and workers’ homes late in the evening, eating dinner with a recorder, passing it around and talking to them about the crisis that they're facing, like, those are the most transformative, emotional, and compelling moments that occur between me and the people that I'm representing in my work through me as a messenger and a platform and an artist to share their story and their vision in their lives with this society.

So that one mindset that perhaps it isn't a physical building or a space. That it simply is the work that I've already been endeavoring to do, which is, be a walking institution and view everyday working people as institutions themselves and to continue to show up, meeting people where they are, and having these conversations and recording them and then working with them to make the type of depictions and representations and images that they would like to make. And in that way, that then becomes an archive. And that archive perhaps is what could then go on to a university, whether that be a HBCU or to a leading research institution. I've worked at every university level possible. I've worked in community centers and churches. So, I really think it's about finding that right partnership.

And then the second approach, I'm from a place where it's too toxic and unsafe for me to return. In a lot of ways, I am in exile from my own hometown, and community, and family. I've been on the road making this work for more than 25 years because it's not safe for me to return home for a multitude of reasons. In that sense, I'm like an artistic insurgent that goes wherever I'm called and you will see this in the exhibition where I'm called into various places, whether that is from Pittsburgh in the steel industry to Flint, Michigan, and automotive industry, to a place like the Borinage, which is the coal mining region of Belgium, to California with Dolores Huerta. So, I'm really deploying myself into these places.

At this point, I would like to be able to settle down and be embraced in an actual local community and to be able to work with elected officials to perhaps purchase a property or a building so that I can then shape into the type of photo center and cultural center that it needs to be. The vision that I have is that it would combine art and healing so that it would allow for it to be a space where people can come and learn about the power of photography, the power of telling stories.

I often think about this discrepancy that we have in society where, in particular in Lordstown, [Ohio] those auto workers had a gag order. They were not allowed to come out and demonstrate and speak while they were still working on the assembly line of the [Chevrolet] Cruze sedan vehicle and that's why you see someone like Werner Lang, who appears standing outside carrying his 40-day vigils. You see me make the portraits of him protesting because he's speaking up for the people.

I think one of the great contributions I could make to this country and society is creating a cultural center that is a place and a space for everyday Americans to come to talk about their work, their labor, their lives. Somewhere where they're not being seen in conflict with their employer or in conflict with local elected officials. What would it mean to this country and society if an artist were permitted to create a space in an archive, where suddenly CEOs and politicians could come and really learn about how their policies and the things that they say in mass media are impacting the general public or impacting the workers without creating division and strife.

My work really does look for peace, love, and justice through unpacking the power of photography as a platform for art, social justice, and cultural change.

Charlotte Burns: Tell me about the audience. What you want with these immersive installations at MoMA? Talk us through what we're going to see.

I know you think very much about who the work is for and what the effects are when you make the work, so what are you thinking in this instance?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Yes. Let's start with the title itself.

Monuments of Solidarity is not about a statue or a physical space. Solidarity is an action. So the exhibition immediately conveys to the viewer that I need you to act, right? It's a proposition for you to think about what does it mean to take action? What does it mean to take collective action? What it means to think about others in the community, and in particular, what it means to think about things that are larger than yourself. So Monuments of Solidarity is not about thinking about a statue of a human figure, but the love that we enact for people, and for people that we may never meet or never know. And for people that may not necessarily be able to do something for us. What does solidarity look like when you look beyond yourself?

Monuments of Solidarity is a rare art exhibit where the people depicted speak back to the audience. As the viewer walks in, they're going to see The Notion of Family, which is a body of work that shows my coming-of-age story in a steel town as a little girl trying to negotiate my voice, how I see myself in my family, my community, and in the world, right?

I think all the time, everyday Americans are thinking about this. We're constantly negotiating how to see ourselves. What does our self-portrait—in the way that we're engaging with our families, community, and society—what does that look like? And how do images and stories that we tell ourselves about our lives, and what we represent, and where we get our start, how that places us within the greater context of society and enables us to make a type of cultural impact to the greater public?

And so in The Notion of Family, that's what you see. It's my coming-of-age story as to what it means to move from being a child and a teenager in a post-industrial landscape, in post-Reaganomic era. And as a little girl, I'm not aware of any of that language or what these policies are, but they are surrounding me. Through that first room, the viewer gets to experience and see all of those things that I'm grappling with, right? I was born into that context and space. It's not something that I asked for, but I needed to visualize that through portraiture, still life, landscape, so that it becomes visible and tangible. I'm trying to harness how you make visible history that's constantly surrounding you and through each portrait, transforming my life my identity, and my voice, one portrait at a time.

From there, you move into that second room and you see where I come outside. It's no longer the portraits of my mother and my grandmother. I start to deploy myself amongst the elders of the community. In the activist group called Save Our Community Hospital, where I'm photographing them demonstrating and protesting the closure of our hospital.

And then of course this forces me, after coming from out of the house onto the street, to then go up into the air and get a bird's eye view on these situations so that the people who are living amongst all of this new redlining, rezoning, and new redevelopments that are impacting their lives and their livelihood, so they can finally see how it's all taking shape around them, and it sets up these important questions around who lives in a place and who gets to control the way that it's shaped. Then suddenly you see the impact of government neglect and abandonment as well as the denial of American democracy—which is the Flint water crisis.

The works become more confrontational and activated in a way where they stand on their own authority through these formal architectural, and sculptural languages of looking at the atmospheric water generator, which is a machine that was used to create, clean, safe drinking water for the residents of Flint. It moves from the photographs themselves documenting and archiving the situation to echoing those interventions and in particular that generator that stands on stilts. The portraits of the people who are drawing the water from the generator are now themselves standing in this very—I guess it's confrontational, in a way–stance with this concrete staring directly at the viewer.

And then there are direct testimonies where they're telling you exactly what it's like to live without clean water and then it continues to move, introducing more and more characters, in particular women who are at the forefront of making all of this grassroots activism happen, where they are circumventing their local government because they can no longer trust, lean on, and rely on them. It requires us to take grassroots action ourselves in the meantime of waiting on justice to come forward.

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: I can't wait to see the show.

As you were talking, I was really struck by that journey that you've been on that now you're putting the viewer into. It's another evolution in your work.

Preparing for this interview, looking back on The Notion of Family, I was struck by how young you look. Now I have a daughter. I think I looked at the family dynamics in a different way and can see how you're navigating those relationships and finding your own power. I was so struck by the tenderness and frankness of them as well as this clear need that you have in your work to talk about something, to say something,

in a conversation with the people around you.

At first, that's you finding your own vision through that. You took that vision out from your own home, onto the streets, and then up and gave it back to people so they could see. Now you're bringing that into the institution and reflecting it back on an audience that may not typically see. So it seems that this is an ever-growing, ever-evolving sense of the possibility and potential of what the camera can do. That act of photography, the collaboration.

Your art is such a bridge between social documentary and conceptual photography, this idea of taking theory and putting it in people's lives. It just moves in terms of your sense of what it can do. And this show seems like a further step in where you can take it, where you can extend it. And I wondered if you could talk a little bit about when you feel aware of that power of the work itself. Are you aware of that as a conscious thing? Or is it something that just develops in and through the work?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Let me back up to what it is that I'm actually trying to do, what my obsession here has been, because it's two things really that are the driving forces. Being an undergrad student, being in my photography course, my intro class, and seeing the two photographs that I think were important for me, which was Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother and Gordon Parks’ Portrait of Ella Watson. When I looked at those two images, it's not that I saw a representation of a figure by a photographer. As soon as I looked at those images, I immediately was struck by what I saw as structures of power. I immediately saw a schematic, a diagram overlaying it, floating above the actual image that was saying to me, “Oh, there's an opportunity of a paradigm shift here.” If you imagine this overlay, over top of Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother, what I see in that image is a triangle. At the top, it's the government and the corporation, who are the ones benefiting from the existence of that image, right? That image is created to say that the President's policies worked. That's supposed to be the evidence for the government and the corporation. Then at the bottom left-hand side is the photographer who is commissioned and yet that photographer isn't getting to contextualize or frame the information or the narrative around the image because it's proliferated and used as an iconic image, but yet it doesn't have the voice of the woman and the children depicted, nor does it have the photographer’s field notes. To the right of that is the subject themselves, a mother and her three children. They never receive any royalties, and they don't get to have a say over how it's depicted, contextualized, and disseminated into the world.

For me as a student thinking about the images, it really is that question of how to take an image, rotate that paradigm, or invert it, so the subject comes first, the photographer comes second, and then whatever structural entity it is comes third. A complete inversion of it that allows the people depicted to narrate, author, and benefit from that image. That is the driving force behind all of the work for 25 years and that's what I've been trying to build into an actual sustainable practice.

But you have to start somewhere and it started out with these singular portraits, still lifes, and landscapes. But then I started taking more initiative and authority about the type of narratives and storytelling that would be around it. And then another step further, which is where Gordon Parks comes in.

In that image of him and Ella Watson, what you're looking at is the relationship of the photographer and the sitter who are both trying to exist and see each other's humanity in a segregated Washington, D.C. This is our nation's capital where these two Black figures are negotiating their rights and their citizenship through looking at each other and acknowledging each other's existence, right? That's a relationship that's key. And I think what Gordon is saying to someone like me or between that collaboration of Gordon and Ella is, what is the value of a Black woman's life in America? How am I going to navigate this? Perhaps it's not about a negotiation, it's about me really taking initiative and authority and writing myself into the history.

When it comes to Braddock, if you were to Google it, you wouldn't know that it was predominantly Black. You wouldn't know that someone like me is from there. I had to, through The Notion of Family and all the photographs, write myself into that history—one portrait at a time, one still life at a time, one landscape at a time—writing my grandmother Ruby, and my mother Cynthia into that town's history. Otherwise, if I didn't, it would still be the continued grand narratives of Scotsmen like Andrew Carnegie and the first settler, John Frazier. That is the story that they tell about that town, when in reality, it is predominantly Black due to systemic, spatial, and structural racism. And we have to continue to write that history into existence so that we understand the legacy that town is coming from, which is actually shaping US history.

So for me, it gets down to that simple question, thinking about those two images and those two great photographers; well, what would Florence Owens Thompson’s self-portrait have looked like had she photographed herself. And I have been pursuing that for many years. It started with The Notion of Family which allowed me to branch out and work with all of the other families that you see me working with now. But then the next step, if Gordon Parks is using his camera to fight back against racism and bigotry in the 20th century, then it affords me that opportunity to use my photographs, right? Not my camera. Use my photographs as a platform for social justice and equity.

And that's what you see that's starting to happen where I really am unpacking the power of photography, not only as something to raise awareness or tell a story, but literally as the platform to advocate for social justice and literally as the resource itself that would bring about the monetary difference so that the people in the work can enact the change that they need. And it also underscores that they actually are the change they need, and that the photographs then become the resource for them to enact that change. And that's the through line that's happening in this work and why it's starting to become larger and more robust and it really starts to become the answer and the solution, right?

It's the creative solution to the situation at hand that the work is revealing to the viewer.

Charlotte Burns: That's the thing that's so compelling about Flint Is Family In Three Acts is a work that you produced over many years and it culminates with you using the proceeds of your gallery sale of the photographs from the first two acts to buy the machine that will bring clean water to the town with a fund from The [Robert] Rauschenberg Foundation and to do something that no government did, no water body did, nobody did. That collaboration between you and the people you were photographing, the town you were in, created the means and created the water.

And it's amazing to hear people talk—and you write about this—because it's not just the photographs. They're accompanied by your writing, which sometimes is plain document of a moment and sometimes is lyrical and poetic and sometimes is testimony, people's words. Especially with the Flint water pieces, hearing people describe the sickness that they felt showering in unclean water and then saying things are so simple, like “I feel strong and I feel healthy,” “I feel speed in my body,” because they can wash with clean water. It's so amazing to think that all came about through the power of the creative act and the collaboration between everything you did.

I want to come back to the catalogue for Flint because you began your essay to that catalogue with a quote by James Baldwin. I know you come back to James Baldwin a lot in your work. I wondered, do you want to read that quote for people?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Yeah, I do. I have it.

Charlotte Burns: Can you read it? Do you mind?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: I'm going to take a sip of water. I think I'm now settling into a groove with you. So I'm feeling good that we can start really digging through all this stuff now.

So, artists, my students, or whenever I'm out giving talks, they're like, “What is my role?” I think we're constantly negotiating and trying to figure out what is the role of an artist is in society. And I think that the person who says it the best is James Baldwin in his essay, The Creative Process, that I believe he wrote in 1962.

So when young practitioners, young artists, young photographers are meeting me and they're like, “I don't really know what my purpose is or what my role is,” “I'm not really sure what I'm really doing here,” I have them print this speech by James Baldwin out, and I say, “Put it on your wall, put it on the mirror. Read it every day,” because I think he's being very clear about what the role of an artist is in society and how different we are from all of the other institutions that exist. And so I'll share an excerpt from it, and this is my mantra and my manifesto, is what this means to me. And Baldwin writes:

“The artist is distinguished from all other responsible actors in society—the politicians, legislators, educators, and scientists—by the fact that he is his own test tube, his own laboratory, working according to very rigorous rules, however unstated these may be, and cannot allow any consideration to supersede his responsibility to reveal all that he can possibly discover concerning the mystery of the human being. Society must accept some things as real; but he must always know that visible reality hides a deeper one, and that all our action and achievement rest on things unseen. A society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven. One cannot possibly build a school, teach a child, or drive a car without taking some things for granted. The artist cannot and must not take anything for granted, but must drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides.”

I'm literally following his instruction in each body of work that viewers will experience and witness. You see me unpacking what he is saying about our role and position. And I believe that my work has always run parallel to mass media. It has always run parallel to the way that elected officials are governing their municipalities. I see my role as an artist as offering an alternate route to what some of these other larger structural forces are in this country that people have to negotiate every day. For example, why should the people of Flint pay the highest water bills in this nation for toxic, contaminated water?

Charlotte Burns: It's appalling.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: But as an artist, as you can see, the role that I play by coming in to shoulder the water operation with Amber [N.] Hasan and Shea [S.] Cobb, I'm providing an alternative solution. I'm working with two mothers and artists and activists in Flint to circumvent their local elected officials who didn't care to bring access to free, clean water because they had to be bound to their political party, and to the larger structure for the roles that they play within politics. Whereas everyday people who are trying to survive these discrepancies in their mistakes, or when racist policies and institutions are impacting their livelihood and their basic human rights, when they have to be confronted by that, you have to do that in a more grassroots way to circumvent and offset that.

And so, as Baldwin is saying, the artist is distinguished from all other responsible actors in society, right? We are separate from politicians. We are separate from legislators. We're separate from educators. We're separate from scientists. And as my own laboratory, I can show up in Flint, Michigan, and use those photographs to tell the story, then stand on them to raise the resources, and then use them to get the technology that they needed to their city, and circumvent that government, and put it on land that was owned by their families, because they didn't want to help them.

And so I think that Baldwin is right when he's declaring in The Creative Process piece that we're not here to serve the requests or the demands of these institutional entities. We're not. That's not our role.

Charlotte Burns: How did it feel for you when you got to the end of Act Three? When you did that, you went, you were your own laboratory, you took the photographs, you raised the resources. You had this outcome that was a victory in every sense. You've documented what it did for the community, but I wonder what it did for you. How did that feel?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: On a personal level, it brought me a sense of peace. Shea's daughter Zion was eight years old at the time that I arrived to Flint and what they didn't know—because I was new to their life and a complete stranger—was that, like Zion, I was eight years old when my hometown also had contaminated water and needed its water pipes replaced. And so it was like a poetic justice. It was bittersweet because through making that work for five years with Shea and Zion, I was able to get the justice that my family was denied and that I was denied as a little girl through showing up for Shea and Zion. And so that made me feel good to be able to stop the type of slow violence that [former] Governor [Rick] Snyder and his administration inflicted upon Zion without her even knowing it because she's a little girl. She's a young girl that's just starting to dream and have her life and her mother's working so hard to protect her and shield her from this. So to be able to say, I'll stand there with you shoulder to shoulder and ensure that I am thwarting this type of pernicious, institutional, racist behavior at the hands of the state and the government was important. And I felt a sense of pride and retribution being able to do that.

The other thing that made me really joyful and happy is that when people see Act Three, I switched the color. They become much larger and activated and suddenly you see, like, all the people who are really involved. When you think about, in terms of our consciousness of how the water crisis was covered, I don't think that we'll be able to recall or say that we saw images like mine. This is the story that mass media neglected to tell. And here's the story.

In the fifth ward of Flint, Michigan, local residents and outsiders that are Black, white, Latinx, South Asian, that are Christian, Catholic, Muslim, Atheist, Queer, Heterosexual, scientists, inventors, artists, and veterans, all came together to work toward a common basic human right, and that is to distribute safe, free, clean water daily across the city of Flint. It's important that images like this from Act Three were disseminated. You realize that Acts Two and Three from Flint were never published in media outlets here in this country. No editor or magazine outlet wanted to publish those images. And that's something that I had to get around not only as a photographer but as an artist, and this is why you see my photographs are not simply documentary photographs. It's not photojournalism, it's art. It's art and activism because of the fact that our own channels that are supposed to be to create images and tell stories like this to help our country heal and come together, refuse to do so. They don't believe that this is newsworthy. So here's the alternative route. A photographer and contemporary artist coming into the Museum of Modern Art in order to share this story for the first time. Like it is the 10-year anniversary tomorrow [April 2024] for the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. And this work has not been seen by an American public and will not be until the Museum of Modern Art opens this show on May 12th…

Charlotte Burns: Wow.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: …for them to see.

Charlotte Burns: That says a lot. It's very damning.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Yes.

And my work is. It's a human document that shows how people resist inequality, how resilient people are, how creative they are despite our own laws and governments coming against us. That we remain steadfast and in grassroots collective solidarity and unity, get the things done. But the role of an artist to come in to make visible and tangible to people that possibility. It's so vitally important. Like my work, it's so much about justice and love and the fact that we can achieve these things together. And not only that, it really calls for new futures, right? A new way of living. It starts to propose these ideas of different ways of living right under neoliberal capitalism. It's the privatization of everything right from your education to your health care to water and in Flint Is Family In Three Acts, you see the possibilities of what life might be like if we reprioritize some of our values. It doesn't have to be this way. Neoliberal capitalism comes into existence in the 70s and 80s. So to me, that tells me there's a possibility for other ideas, other economic theories. Trickle-down economics failed in this country. And this work is an indictment on that. And it reveals it and it shows it. But it also shows that people are already working on other solutions. And that our governments and elected officials and policymakers could learn from looking to the very people who are sitting at these intersections of all the calamities that their policies created.

Charlotte Burns: Your work shows that people are always coming up with other solutions—communities coming together, this idea of solidarity, of people working together to achieve things in spite of, despite, has always been the case. And you're photographing that narrative. It's a future way of doing things, but it's not a brand new way of doing things. It's the way people have been doing things and are doing things up and down the country every single day. That exposure, this is what your photography can do.

You have a quote in one of your catalogues, “Part of the root of the word photograph is phos, which means light or to shine. The ancient Greek phosphorus, means bearer of light or bringer of light”. You have this line—which I loved—where you said, “The light shines in the darkness and the darkness has not overcome it.” And the idea that these images shine a light into an alternative and the kind of power of that is, as you can see, it moves through communities. It moves through people. It that has real tangible effects.

I know that Frederick Douglass is someone you've looked to and he noted photography's potential for shifting things in a speech he gave in 1865 [1861], “Pictures and Progress,” where he said, “Poets, prophets, and reformers are all picture makers, and this ability is the secret of their power and of their achievements. They see what ought to be by the reflection of what is and endeavor to remove the contradiction.”

You said the mind is the battleground for photography and how your mind had been deceived and deluded, but your images can change that. And that idea of shedding that light and bringing different people into that picture is so powerful.

When you go through your show at MoMA now, do you feel in conversation with those past bodies of work yourself like the audience would? How does that feel to have that moment to bring these things together?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: This feels like a massive triumph, but a triumph for the people, right? It's not about me. This is so much larger than me. And I feel like seeing it come together that I really have carried out the purpose, meaning, and the will that was predestined for my life. In a spiritual sense, I was obedient to what I believe I was called to do and in that way, I feel very proud to have been a servant.

I see myself as a servant and as a messenger for the people of this nation. And in particular, for people from the industrial heartland of America and for all working people around the globe that don't see themselves praised in these types of elite spaces. And who don't see themselves written into the histories next to these large, industrial capitalists that they've made wealthy and made fortunes for.

So for me, I feel not that the work is completely finished, but that I definitely have achieved a large bulk and a large part of finding out who I am. We're all wondering who we are and what we would like to do and who we think we would like to be and what we need to become in order to bring about change and justice. Like I am a firm believer that whatever era you were born in, whatever situation you were born in, it is better to use your life as a gift of love and service to make it better than what it was when you were brought here.

And so Monuments of Solidarity for me as a survey show, looking at the past quarter of a century of my artistic practice and production, it's a triumphant moment. To say that I started from a place called the Bottom, literally. I'm from a place in my hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania, called the Bottom and now I'm all the way here, at the height of one of the most prestigious national museums making sure that all of these families that I've been advocating for 25 years are seen at this high level. And in that type of realm, I feel at peace and I feel like I've carried out a big part of the mission.

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: Can you talk a little bit more about your faith? The title for your essay is Photographed by Faith, Not by Sight. You just talked about yourself as a servant in this spiritual practice. Can you tell me a little bit more about your faith system, what it is you have faith in? I know you have faith in the subjects. I know you have faith in the work itself. You quote religious texts in the catalogue essay. Can you talk us through that faith and how important that is for you because there's a level of endurance to the work that I'm sure is taxing upon you and must require faith.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Yes. If you don't mind, I'd like share a part of my favorite scripture that I'm always using in order to carry out my work, and that is an excerpt from 1 Corinthians, Chapter 13. In that spiritual sense, I'm thinking about faith, hope, and love— understanding that love is the most important, and what that scripture teaches is that:

“Love is patient, love is kind, it does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud, it does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking. It is not easily angered. It keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil, but rejoices with the truth. It always protects. It always trusts. It always hopes. It always perseveres. Love never fails. And now these three remain. Faith, hope, and love. But the greatest of these is love.”

And I think being from an area called the Bottom, being raised by my grandmother, Ruby who, in order to protect me, kept me either in school or in church—where she raised me as a Baptist Christian—I think I'm also paying homage and respect to her, for how she provided care and protection for me so that I could survive one of the most tumultuous times in this country, which was, again, under Reagan's administration. Them inflicting the war on drugs upon our Black working-class communities after all our jobs were exported and social services removed. Right at that moment when Black workers were starting to be involved in labor unions and getting these better jobs and better positions, this is when it all gets stripped away. And so we lose a part of what we were starting to amass in terms of being able to get some type of semblance of an equal footing with our counterparts in this country. It's taken away from us in that moment. And it has to be, for me, surviving that era through the faith and spirituality that I learned, from how she raised me.

I've always seen myself, as a little girl who had so many questions about what was happening to Braddock's landscape and environment, I've always seen myself as this entity, as this human spirit that is walking through all of these valleys, these very dark valleys. Braddock is in the Monongahela Valley. Flint, Michigan is in a valley. Lordstown is in the Mahoning Valley. These are all valleys, all along these ancient bodies of water that are actually spiritual names, when you translate them to English. And there are these sacred people that are in these places, that our government has forgotten about, that our society has forgotten about, that we exist. They're there, and I see myself as someone who is walking through these dark valleys and capturing the light that's reflected from the people that are there.

To me, all of the men, women, and children in Monuments of Solidarity and all of the bodies of works, they are all prophets and apostles of this era. Even Flint Is Family In Three Acts as a book is designed and based off of my amplified Bible. So literally, you are hearing what really happened in the Flint water crisis, first person, through Shea Cobb, through her father, Mr. Smiley, through her best friend, Amber Hasan, and Moses West—his name is Moses, and he's made an atmospheric water generator.

To me, every single person that I have made a photograph with and interviewed, they're that precious to me. And that's where the spirituality also is enacted with how I'm treating their voices, weaving all of their narratives together so that it becomes one voice, one accord, one choir of voices harmonizing together to uplift each other's humanity.

Charlotte Burns: I love that. That choir. I got a real sense of that as you describe the spaces in this show and also this idea of the institution you have in your mind as a convening place for more voices and more testimony, more gathering, and more archiving.

Also, obviously, the solidarity is taking place in a cultural institution when there's so much unionization happening in cultural institutions. MoMA's had a union since 1971. There's much more unionization happening in the art world itself. Is that in your thoughts as you make this show about solidarity, thinking about the specific cultural institutions and specific cultural workers?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: One thing that is important to celebrate when this exhibition opens, the reason this show came into existence is because of MoMA's decision to acquire The Last Cruze.

The Last Cruze is a worker's monument. That is about the history of the United Auto Workers Labor Union and in particular locals, 11, 12, and 17, 14 in Lordstown, Ohio. While I was in the midst of making that work, it was serendipitously during that moment that MoMA's workers joined the UAW, the United Auto Workers labor union, and of course, providing that opportunity to MoMA to acquire a work that speaks to its workforce and acknowledges its workforce. The fact that they had the courage and the sensibility and sensitivity to acquire it, and not only acquire it, mount an entire survey exhibition around it to reveal it to the general public. You couldn't ask for more as an artist. I mean that really is the work doing the work, right?

Charlotte Burns: So if we take that one step further, if you manifested that reality then, I wonder what reality you want to manifest with this show now.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Yeah, I'm pretty excited about it as it's getting closer to the show opening because that remains to be seen, but I am aware of that. If MoMA was able to hear my plea to bring this worker's monument into its permanent collection—and did it— yeah, I think the sky's the limit. Yeah, it remains to be seen.

Charlotte Burns: But what if you could put it in the universe? What if you could manifest that? What would it be for you?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: I really need to think about that for a second. You came in pretty fired up. That was your first two questions was exactly where this now leads us to.

I believe having this exhibition open here with the backdrop of a very tumultuous, political election occurring is not a coincidence. I think that the timing of this exhibition being revealed right now when America is in so much turmoil and conflict really does shed light on the importance of artists being a mirror to our society, as well as artists being the soul of our nation, and as well as why we need art in our school systems and why we need to value artists.

One thing that this exhibition certainly is going do is it's going to impact people personally and emotionally. I don't think that anyone that experiences Monuments of Solidarity, by the time they walk through all 10,000 square feet of this space, of all ten rooms, they will not come out the same. This exhibition spiritually uplifts people. It inspires people to be the change they need but it also inspires them to be better human beings, to look beyond the self, to look beyond individualistic desires, to think about the fact that you are connected to an ecosystem and a world around you. People won't be the same. This is a transformative exhibition. It is an exhibition to be experienced, to be transformed at your core. And I believe it's not necessary to argue with people. Sometimes you don't need to say anything with words. It's how you show love through creative expression.

I definitely intend to touch the hearts and minds of the people that experienced this and to inspire and encourage them so they know, like, it starts with you, right? It's those little things that you do every day for your neighbor. It's how you show up and protest and speak up for someone else that might not be able to because of a law or policy where they can't defend themselves. If you're in the position of entitlement or privilege, where perhaps neither a Republican or a Democrat is impacting your livelihood, perhaps you cast your vote thinking about the safety and the life and longevity of somebody else, right?

To me, that's what American democracy can be. I am not simply thinking about myself when I cast my vote. I'm thinking about other people who are much more vulnerable than me. So the time is always now to act. The time is always now to look beyond yourself. We do need in this country a real—back to Frederick Douglass, and being a reformer—we need to reform how we mediate and tell stories. We need to reform how we disseminate information to Americans. We need to reform our education system.

We need to reform how we value photographers in this society, how we value photographers in the art world, how we value the very people who are at the bottom, right? We need a real reform of all of these value systems. And this exhibition offers a blueprint, a pathway, and a bridge to achieving that and to doing it.

Charlotte Burns: We often talk about the subjects of your work and the collaborations that you do, but this idea of the impact that the work has, I know you have that people come up to you and they confide things in you. There's this sense of the work never ending and how it moves through the world beyond you and then maybe comes back to you, and changes where you go next. And I wonder, it's such a lot to carry, you carry so many stories. Were you always able to hold that space or is that something that's developed as you've got older, that ability to stand in your own clarity of vision?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: I think it was always there. I think it's undeniable. Your name and the location and place you're born does shape your characteristics and personality.

What I didn't know is exactly what it was that I was attracted to in doing. I was always preaching the word to my mom and her friends. I would go in the bar preaching to people, because my mom and my father were bartenders. I would sit in the bar and listen to people talk about their livelihood or how they feel. Like I've always been someone that believes in empathically listening to others and trying to understand and see the world through their perspective. So my approach comes from that.

In Belgium, where it all started to crystallize for me, I was there with those coal miners, that's when it hit me. They said to me, “Why are you here?” And this is a residency that I was invited to, where they took The Notion of Family out to these coal miners and their families and they agreed to meet me. But yet, when I got there, they still wanted to know, “Why are you here? Why do you care about us? You're an American, you're a woman, you're Black. We've never even met a Black woman before.” And then they say to me, “By the way, contemporary art is useless.” And so as soon as they came to me with those grievances and curiosity—and this of course stemmed from the fact that the MAC Museum [Wallonia-Brussels Federation Museum of Contemporary Arts] is a contemporary art museum in a former coal mine site, and yet it makes no exhibitions that reflect the very people that are living around it. So this is where this gripe came from and why I was being brought in in the first place. And that's when it hit me. I said, “Wow, I'm here to stand in the gap between working class and creative sectors. I'm bridging that gap for them.” I'm from a city of bridges. Pittsburgh is the city of bridges, so I'm naturally a bridge-builder. I am someone who closes gaps and creates opportunity. I am someone that, through art, redistributes power and equity back to the people.

Charlotte Burns: I love that. The way that you describe things, like some of your images. You talked earlier about when you saw Migrant Mother, you had a schema over the top of it and in your images, you often have overlays or it would be a person projected with something around them or on top of them. Or even early photos of you and your mom, there's a sense of shadow and projection in the work. Even the way you talk about Braddock as a historical battleground, where its namesake comes from the British general who was killed. But it's still a battleground, and with the health implications of the toxic, chemical emissions from the steel industry. But overlaid on that is this spiritual battleground that you're talking about too, and that care, and that love.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Mm-hmmm.

Charlotte Burns: Underlayed is the history that came before that. The Braddock that was before any of the steel mills and the Indigenous people and the Black community was there before Carnegie bought the steel mill.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Yeah.

Charlotte Burns: I know that part living in Braddock is that you and your family have all shared illnesses as an effect of the toxic chemicals. Are you living with that okay?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Yeah, these days I'm okay. Like anyone else with an autoimmune disorder living in a post-Covid America, knowing that we're all part of our ecosystem, there are some good days and some bad days. There's a real truth and reality to all of the work. I have deployed my body into harsh environments and so being on the other side of finally installing this work and sharing it with the world, it allows me to get that respite and recovery that I need. After putting my body through everything that it's been through to carry this work forward.

I think every day you get up and you do what you can with your body and your health. I certainly am more mindful of taking care of my health, and my mental health, and my physical health but, autoimmune disorders don't have a rhyme or reason. They kind of shape and shift and you have to go with them. So that is a real reality, and a consequence of my work and the environments that I've been in. But this will allow me to get the respite and to take a little pause and a break that I finally need.

Charlotte Burns: Do you take breaks often? I'm not sure you do.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: I've never taken a break or a vacation.

Charlotte Burns: Wow. Wow!

LaToya Ruby Frazier: When I open this show, this summer will be probably one of the first times that I really do take a vacation. I think I've earned the right to finally take my first vacation where I just sit down and do nothing. I'm not good at doing nothing but it'll be nice to take a real official vacation and try to relax.

Charlotte Burns: Talking of deploying a body into difficult spaces, can you tell us more about your projects looking at community health workers?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Yes. [The More Than Conquerors: A] Monument for Community Health Workers of Baltimore, Maryland [2021-2022] came into existence when I deployed myself into Baltimore on the front lines of Covid with community health workers. They are an invisible workforce, and I learned about them through Dr. Lisa Cooper, the founder of the Johns Hopkins Health Equity Center. She and I had been brought in in 2015 at a program where we were asked what could happen if a doctor and a scientist and an artist work together? How could you make a work together that could be useful to society? Several years later, in the midst of the pandemic, is where the collaboration happens. And she introduces me to this wonderful community of community health workers. And I decided to go out there and make portraits of them and interview them on the front lines of Covid.

One of the things that I think is important that was achieved in this monument is what it was able to do, how it was able to impact the art world. I want to uplift Evelyn Nicholson in particular, a community health worker who was working at the University of Maryland Institute of Human Virology. She specialized in working with patients and clients with HIV. She herself had HIV, was a participant in AIDS Act Up. She devoted her whole work and life to advocacy, to standing up for people with HIV and AIDS—especially those that lived into being elders. Because remember, there was a bias: people didn't believe that someone with HIV and AIDS could live that long. You had a disproportionate number of them during Covid that were susceptible, but also, dealing with homelessness. So in the midst of that, Evelyn Nicholson is out there meeting with them, empowering them, listening to them, helping them get access to their medication, helping them get access to food. Baltimore faces these high levels of food deserts, and all the different inequalities that happen there that impact social determinants of health.

So Evelyn herself is wearing a t-shirt in the portrait and you'll see this in Monuments of Solidarity. There is a dedication to her and her portrait comes up. And in this exhibition, I want people to know these monuments are monuments for people who gave their lives and died by serving their communities.

Evelyn passed away. What's important about learning about her testimony and her story and how she showed up for people in the midst of dealing with her own illness, the fact that she came to all of the openings at the Carnegie International, and then she came to the one Gladstone Gallery in New York. And here's this beautiful moment where all of this comes full circle for how we all show up for each other in the art world.

The collector, Mitch Rales comes into the exhibition. Evelyn is standing next to her portrait, and I introduce her to Mitch and she's talking to him about her life, and her activism, and her work. I took a portrait of them, and I kept it. A few months later, she passed away.

I believe that it was through making this monument where it brought two unlikely people together, Evelyn Nicholson and a collector like Mitch Rales, who are standing at this exhibition in the gallery. And they're getting to know each other and they impact each other. Clearly, Emily and Mitch Rales’ through, Glenstone, care a lot about art and community and we created a relationship and a friendship through them experiencing this monument for CHWs.

I believe that it was their encounter with Evelyn Nicholson in particular that suddenly planted the seed that allowed for the Rales to come forward to collect and acquire the Monument for Community Health Workers of Baltimore, Maryland and do what I had hoped could be done; to ensure that those CHWs would be honored in their local community. That monument would return to Baltimore itself so that those workers, their families, they themselves can see themselves honored on a national level of their local museum. The Monument for Community Health Workers of Baltimore, Maryland will remain a permanent fixture of Baltimore. And this is a rare opportunity in a rare time where you see a contemporary artist working with a gallery, working with powerful collectors and dealers in a gallery to ensure that everyday working people would be honored and respected and elevated to the level that they deserve. And I think this is the power of art and the role that artists play.

The fact that this is a worker's monument that will now remain a permanent fixture where they could be celebrated for the rest of their lives and someone like Evelyn Nicholson will never be forgotten.

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: Okay, so what's the ‘what if’ that keeps you up at night and what's the one that gets you out of bed in the morning?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Oh man. So how do I want to answer this? I think the question for me is… yeah, what if Monuments of Solidarity really did become an institution and a pedagogy that really could impact cultural change? What if the values that a Monuments of Solidarity puts forth really does become activated in a way that it can bring change to our culture and society and how we relate to each other. What would happen if we valued photographers better in the art world? What would happen, the impact that I could have on the art world and the general public if the type of artwork that I make was really financially supported so that I could really get back out there in the world and on the ground to keep helping impact people's lives? Like what would that look like if people valued my artwork and my photography and storytelling at the highest level? What would happen? What I could do all the things that I could achieve if I had the real support at the highest level? I know that I could bring about tremendous cultural change if people really did support the practice financially and so, what if the art world really did get behind valuing work like mine so that I can get back out there on the ground with people and bring real change? That's what I think about.

Charlotte Burns: LaToya, what a great question to end on. I have so enjoyed talking to you. Thank you so much for making the time to talk to us today. It has been an enormous privilege and pleasure to talk to you about your art and everything that you are doing. It is so powerful and so meaningful and I cannot wait to see the exhibition.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Well, Charlotte, it's been a real pleasure speaking with you and speaking with the audience for The Art World: What If…?! Thank you for taking out the time to speak with me and disseminate some of these ideas and thoughts into the world. It's been a real pleasure talking to you. Thank you.

Charlotte Burns: It has been such a pleasure LaToya. Good luck with the install.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Thank you. I can't wait for you to see it and experience it.

Charlotte Burns: I cannot wait. I cannot wait.

[Musical interlude]

Charlotte Burns: What an artist! My huge thanks to LaToya Ruby Frazier who so generously gave us so much time during install.

And if you’d like to hear more about Glenstone and the work of Emily and Mitch Rales— as LaToya mentioned—you can find that episode in our first season, in our back catalogue.

Next time we have a special museum show, focusing on the change that comes after the storm.

“It’s also about treating people like actual human beings and I think that lone-wolf leadership model doesn’t work anymore. People know that but they don’t know how to get out of it. The part about the collaboration that is so critical is that for leaders that are effective, they know how to work with a diverse range of people on a diverse range of issues and bring people together in difference which is pretty fundamental.”

“I think different kinds of institutions can be fixed in various degrees. One of the challenges of talking about the cultural field is that you have so many different kinds of players in it so a small organization like Recess in Brooklyn is going to be able to make different kinds of changes than say the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Louvre or the British Museum. These are monumental institutions. They’re like changing a cruise ship or an aircraft carrier’s direction rather than a small sunfish.”

Charlotte Burns: Such a thoughtful and interesting conversation to come. That’s next time on The Art World: What If…?!

This podcast is brought to you by Art&, the editorial platform created by Schwartzman&. The executive producer is Allan Schwartzman, who co-hosts the show together with me, Charlotte Burns of Studio Burns, which produces the series.

Follow the show on social media at @artand_media.

Share this post